Glioblastoma, a highly aggressive form of brain cancer, presents significant challenges in patient care due to its poor prognosis and debilitating symptoms. Patients often endure substantial neurological decline and suffer from adverse effects of aggressive treatments. Integrating palliative care early in the oncology care trajectory is widely recognized for its benefits in improving quality of life and managing symptoms for advanced cancer patients. However, despite these advantages, palliative care utilization remains notably low among glioblastoma patients. This article delves into the critical question: Is There A Validated Tool To Increase Palliative Care Referrals for this vulnerable patient population? Based on a quality improvement project, we explore the feasibility, value, and effectiveness of implementing a tailored palliative care screening tool in an outpatient neuro-oncology setting to address this gap.

The Imperative for Early Palliative Care in Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma, classified as a World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV glioma, is the most prevalent primary malignant tumor of the central nervous system. The prognosis for patients diagnosed with glioblastoma remains grim, with a median overall survival of just 12 to 15 months. Throughout their illness, these individuals face a considerable decline in neurological function, leading to a complex array of symptoms that place a heavy burden on both patients and their caregivers.

The palliative care needs of glioblastoma patients are particularly intricate. They often grapple with functional, cognitive, and communication deficits, along with symptoms such as drowsiness, cognitive impairment, aphasia, motor weakness, seizures, and personality changes. Furthermore, treatments like chemotherapy and radiation therapy can exacerbate their distress through side effects like nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and further cognitive decline.

Research consistently underscores that despite the high symptom burden experienced by high-grade glioma patients, they are less likely to receive palliative care compared to those with other cancers. Several factors contribute to this disparity. Patients and families may mistakenly believe palliative care is solely for end-of-life situations. Healthcare providers might equate palliative care with hospice, fearing it diminishes hope. Crucially, a lack of clarity and consensus among healthcare providers regarding palliative care referral criteria stands as a significant barrier.

The Evidence Supporting Early Palliative Care Integration

A growing body of evidence highlights the profound benefits of integrating palliative care early in the management of advanced cancer. Studies have demonstrated that early palliative care interventions lead to improved quality of life, reduced mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety, and even decreased healthcare costs. Despite this increasing recognition, a significant gap persists in the practical implementation of early palliative care, primarily due to insufficient referrals from healthcare providers.

To overcome this referral hurdle, research suggests that utilizing screening tools to proactively identify patients who could benefit from palliative care services is highly effective. A study by Begum (2013) demonstrated a significant reduction in the proportion of patients not referred to palliative care, dropping from 68% to just 16% within a four-month period following the introduction of a screening tool.

Clinical guidelines from esteemed organizations like the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) strongly recommend that outpatient oncology programs integrate palliative care resources for cancer patients experiencing high physical and psychosocial symptom burdens. The NCCN guidelines specifically advocate for repeated screening of all advanced cancer patients to facilitate timely palliative care referrals. However, reports indicate that the adoption of these guidelines into routine practice remains limited, with many institutions unsure about referral criteria and timing. This underscores the urgent need for standardized needs assessments to effectively promote palliative care within oncology settings.

This quality improvement project was initiated to address this critical gap by implementing a palliative care screening tool specifically for glioblastoma patients in an outpatient neuro-oncology clinic. The aim was to increase both the screening rates and subsequent referrals to palliative care for this high-need population.

Project Objectives: Feasibility, Value, and Effectiveness

The primary goal of this project was to evaluate the feasibility, value, and effectiveness of incorporating a palliative care screening tool for glioblastoma patients (WHO grade IV) returning for follow-up evaluations at the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center (PRTBTC) at Duke Cancer Institute (DCI).

Specifically, the project aimed to:

- Assess Feasibility: Determine the proportion of eligible glioblastoma patients screened for palliative care needs using the glioma palliative care screening tool during routine outpatient visits.

- Evaluate Value: Measure the proportion of patients scoring 5 or higher on the screening tool who engaged in a palliative care discussion with their healthcare provider.

- Determine Effectiveness: Calculate the proportion of patients referred to palliative care among those who had a palliative care referral discussion.

Design and Methodology of the Quality Improvement Project

This quality improvement (QI) project was meticulously designed to assess the impact of a palliative care screening tool on referral rates for glioblastoma patients in an outpatient setting. The project underwent formal evaluation using a QI checklist and was deemed exempt from institutional review board review, as it focused on improving existing care processes.

Adapting a Screening Tool for Neuro-Oncology

Initially, a comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify a palliative care screening tool specifically designed for neuro-oncology patients. However, no such tool was found to be readily available. Therefore, a simple yet effective palliative care screening tool, originally developed for general outpatient oncology patients based on NCCN palliative care screening criteria by Glare, Semple, Stabler, & Saltz (2011), was selected for adaptation.

This tool comprised five key screening items:

- Presence of metastatic or locally advanced cancer

- Functional status score (using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status)

- Presence of serious complications of advanced cancer (prognosis < 12 months)

- Presence of serious comorbid diseases (poor prognosis)

- Presence of palliative care problems

A score of 5 or more on this tool was recommended as a trigger for palliative care referral.

To tailor the tool for glioblastoma patients, modifications were made in consultation with the neuro-oncology team at PRTBTC. Given that glioblastoma is inherently an advanced disease and extracranial metastases are rare, “progressive disease at current visit” was substituted for “metastatic or locally advanced cancer.” The functional status scoring was adjusted to incorporate the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), which is commonly used at PRTBTC, alongside the ECOG scale. Examples were added to clarify “serious complications” and “comorbid diseases” relevant to the glioblastoma population. These examples were further refined during the project’s initial days to enhance clarity and applicability.

Data Collection and Implementation

A provider questionnaire was developed to collect essential patient data, including age, sex, diagnosis, palliative care discussions, referral outcomes, and reasons for not discussing or referring when indicated.

Prior to project implementation, informational sessions were conducted with clinical staff at PRTBTC, including neuro-oncologists, nurse clinicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), certified medical assistants (CMAs), and clinic nurses. These sessions aimed to familiarize the team with the project’s objectives and the use of the screening tool and questionnaire.

During outpatient visits, CMAs provided the glioma palliative care screening tool and provider questionnaire to APPs. APPs utilized the screening tool during patient examinations, incorporating medical history. If a patient scored ≥ 5, indicating a need for palliative care, the APP discussed a referral with the attending physician and the patient. Referrals were made upon agreement from both the attending physician and the patient. Local referrals were directed to Duke palliative medicine, while for out-of-state patients, recommendations were made for palliative care referral within their local oncology network. APPs subsequently completed the questionnaire to document the screening, discussion, and referral outcomes.

Setting and Participants

The QI project was conducted at the PRTBTC, a tertiary outpatient neuro-oncology clinic within the Duke Cancer Institute in Durham, North Carolina. The clinic specializes in treating adult patients with primary brain and spinal tumors.

The target patient population included adults (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with WHO grade IV malignant glioma (glioblastoma or gliosarcoma), proficient in English, and returning to PRTBTC for routine follow-up evaluations with a scheduled brain MRI. Patients undergoing pretreatment evaluations, new patient evaluations, or those already receiving palliative care were excluded.

The key providers involved in the project were ten board-certified APPs (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), along with physicians, fellows, residents, and medical students. The APPs collaborated closely with supervising neuro-oncologists and communicated care coordination needs with local oncology teams for patients outside the Duke network.

Outcome Measurements

The primary endpoint of the project was to determine the proportion of eligible patients screened for palliative care needs using the adapted screening tool during the 10-week implementation period. This was calculated by dividing the number of patients screened by the total number of eligible patients.

Secondary endpoints included:

- The proportion of screened patients who had a palliative care discussion (among those scoring ≥ 5 on the screening tool).

- The proportion of patients referred to palliative care (among those who had a palliative care discussion).

Data were collected through the provider questionnaires and analyzed descriptively.

Project Results: Increased Screening and Referrals

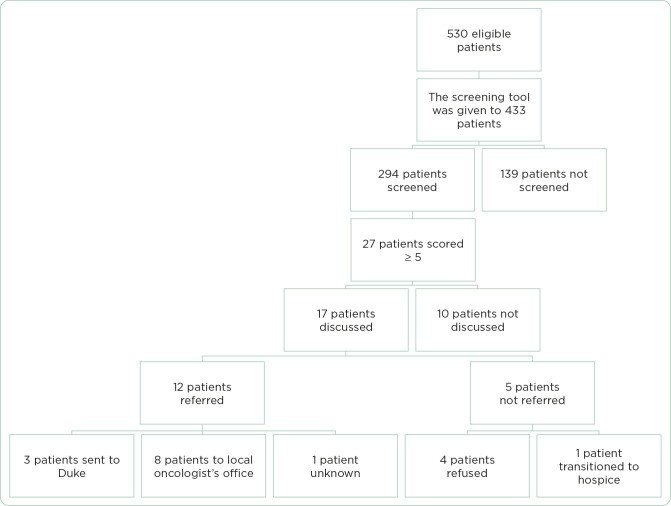

The project was implemented over a 10-week period from September to December 2018. During this time, 530 patients were identified as eligible for screening.

Screening Rates

The screening tool was made available to providers for 433 of the 530 eligible patients. An initial oversight in tool distribution by CMAs during the first 17 days accounted for the 97 missed patients. Among the 433 patients for whom the tool was available, 294 (68%) were screened using the glioma palliative care screening tool. Overall, considering all eligible patients, 56% (294/530) were screened (Table 1).

Value of the Screening Tool: Palliative Care Discussions

Of the 294 patients screened, 27 (9%) scored ≥ 5 on the screening tool, indicating a potential need for palliative care referral. Among these 27 patients, 17 (63%) engaged in a palliative care discussion with their provider.

Effectiveness: Palliative Care Referrals

Among the 17 patients who had a palliative care discussion, 12 (71%) were referred to palliative care services. This represents 44% of the 27 patients who initially screened positive for palliative care needs (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Patient Demographics and Provider Roles

The screened patient population was predominantly male (60%) and generally had a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of 70% or higher (47%). A significant portion (45%) reported a minimal NCCN Distress Thermometer score of zero. The majority of screened patients (53%) were between 46 and 65 years old (Table 2). Trained APPs conducted the majority of screenings (89%), highlighting their crucial role in this process. Other providers involved in screening included fellows, residents, medical students, and attending physicians.

Reasons for Lack of Discussion or Referral

Among the ten patients who did not have a palliative care discussion despite a positive screening score, the primary reasons cited were a focus on future treatment plans (five patients) and attending physician disagreement regarding the need for discussion (three patients).

Of the five patients who had a palliative care discussion but were not referred, four declined the referral, and one was referred to hospice care instead.

Figure 1. Palliative care referral outcomes.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Table 1. Project Outcomes.

| Outcome | Estimate | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of eligible patients screened | 294/530 (56%) | 51%–60% |

| Proportion of eligible patients screened among those for whom the certified medical assistant provided the form to the APP | 294/433 (68%) | 64%–72% |

| Proportion of screened patients with score ≥ 5 | 27/294 (9%) | 5.9%–12.5% |

| Proportion of patients with score ≥ 5 who had a palliative care discussion | 17/27 (63%) | 42%–81% |

| Proportion of patients with score ≥ 5 who were referred to a palliative care consult | 12/27 (44%) | 25%–65% |

| Proportion of patients with referral among those with a palliative care discussion | 12/17 (71%) | 44%–90% |

Table 2. Patient Demographics.

| Gender | |

|---|---|

| Male | 177 (60%) |

| Female | 109 (37%) |

| Unknown | 8 (3%) |

| Age | |

| 18–25 | 18 (6%) |

| 26–35 | 39 (13%) |

| 36–45 | 49 (17%) |

| 46–55 | 84 (29%) |

| 56–65 | 71 (24%) |

| 66–75 | 21 (7%) |

| > 75 | 10 (4%) |

| Unknown | 2 (1%) |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | |

| 90%–100% | 133 (45%) |

| 70%–80% | 123 (42%) |

| 50%–60% | 35 (12%) |

| 30%–40% | 3 (1%) |

| 10%–20% | 0 (0%) |

| NCCN Distress Thermometer score | |

| 0 | 131 (45%) |

| 1 | 35 (12%) |

| 2 | 26 (9%) |

| 3 | 21 (7%) |

| 4 | 17 (6%) |

| 5 | 19 (6%) |

| 6 | 8 (3%) |

| 7 | 8 (3%) |

| 8 | 4 (1%) |

| 9 | 2 (1%) |

| 10 | 3 (1%) |

| Unknown | 20 (7%) |

Discussion: Integrating Screening Tools for Improved Palliative Care Access

This quality improvement project provides compelling evidence that integrating a palliative care screening tool into routine outpatient neuro-oncology clinic workflows is feasible and effective in increasing palliative care referrals for glioblastoma patients. Given the complex symptom burden and known benefits of early palliative care for this population, these findings are particularly significant.

The project demonstrated a notable increase in palliative care referrals compared to baseline data. Prior to the intervention, an average of six brain tumor patients were referred to Duke palliative care per 10-week period, and a pilot study on early palliative care integration showed approximately two referrals per 10 weeks. This QI project resulted in 12 referrals within the 10-week implementation, suggesting a substantial positive impact of the screening tool.

While the screening rate of 56% among all eligible patients indicates room for improvement, the rate of 68% when the tool was available highlights the potential for even greater impact with optimized implementation. The initial challenge with tool distribution by CMAs underscores the importance of streamlined processes. Integrating the screening tool directly into the electronic medical record (EMR) system could significantly enhance accessibility and ensure consistent application. Automating prompts or alerts within the EMR based on screening scores could further facilitate tool utilization and promote long-term adoption.

The project also emphasizes the pivotal role of APPs in driving palliative care integration within oncology care. APPs conducted the vast majority of screenings and initiated palliative care discussions, demonstrating their capacity to champion this aspect of patient care.

It is important to acknowledge a limitation of this project: the adapted glioma palliative care screening tool was not formally validated for this specific population. However, the original tool by Glare et al. (2011) was based on established NCCN guidelines and has been used effectively in outpatient oncology settings. Its adaptation for glioblastoma patients was carefully done in consultation with neuro-oncology experts to ensure clinical relevance. Furthermore, a validated inpatient version of the original tool exists, lending credibility to the core screening criteria.

The reasons cited for not discussing palliative care, even with a positive screening score, point to practical barriers within busy clinical settings. The focus on immediate treatment planning and time constraints can overshadow the importance of addressing palliative care needs. Exploring models that integrate palliative care visits with routine oncology appointments could help overcome these logistical challenges and facilitate a more seamless approach to comprehensive patient care.

Patient refusal of palliative care referrals, observed in a few cases, highlights the need for improved patient education and addressing potential misconceptions about palliative care. Many patients may still associate palliative care exclusively with end-of-life care, rather than understanding its broader role in symptom management and quality of life enhancement throughout the disease trajectory. Future initiatives should focus on clarifying the scope and benefits of palliative care to improve patient acceptance and engagement.

Conclusion: A Step Towards Proactive Palliative Care in Glioblastoma

This quality improvement project provides a positive answer to the question: is there a validated tool to increase palliative care referrals? The findings clearly demonstrate that the implementation of a palliative care screening tool is a feasible and valuable strategy to increase attention to palliative care needs and drive referrals for glioblastoma patients in the outpatient setting.

While further optimization is possible, particularly through EMR integration and enhanced patient education, this project represents a significant step forward in proactively addressing the palliative care needs of this vulnerable population. By utilizing such screening tools and addressing systemic barriers, healthcare providers can facilitate earlier access to palliative care, ultimately leading to improved symptom management, enhanced quality of life, and better outcomes for individuals living with glioblastoma.

Appendix A. Glioma Palliative Care Screening Tool

| Screening items | Points | Patient points |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive MRI at current visit | 2 | |

| Functional status of patient (ECOG score/KPS score) | 0–4 | |

| 0: ECOG 0 = KPS 90%–100% | ||

| 1: ECOG 1 = KPS 70%–80% | ||

| 2: ECOG 2 = KPS 50%–60% | ||

| 3: ECOG 3 = KPS 30%–40% | ||

| 4: ECOG 4 = KPS 10%–20% | ||

| Any serious complication of cancer associated with a prognosis of | 1 | |

| Presence of one or more serious comorbid disease associated with poor prognosis (e.g., moderate-to-severe CHF, stroke, cognitive deficit, renal disease, liver disease, PE, bowel perforation, cerebral edema, obstructive hydrocephalus, cytopenia or NEW active problem requiring intervention or admission) | 1 | |

| Presence of palliative care problem | 1 | |

| • Uncontrolled symptoms (e.g., GI symptoms, headaches, fatigue, rash) | 1 | |

| • Moderate-to-severe distress (NCCN Distress Thermometer score of 4 or higher) | 1 | |

| • Patient/family concerns regarding course of disease and decision making | 1 | |

| • Patient/family requests palliative care consult | 1 | |

| • Team needs assistance with decision making | ||

| Total | 0–13 | |

| Refer the patient to palliative care when the score ≥ 5 | ||

| If the screening tool is not used, please write the reason below __________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Note. ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; KPS = Karnofsky Performance Status; CHF = congestive heart failure; PE = pulmonary embolism; GI = gastrointestinal; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Adapted from Glare et al. (2011).

Appendix B. Provider Questionnaire

| Day # | __________ |

|---|---|

| Age | __________ |

| Diagnosis | __________________________________ |

| Sex | M/F |

| NCCN Distress score | __________ |

| Are you an APP? | □ Yes □ No: Fellow/Resident/Med student |

| Screening score ≥ 5? | |

| □ Yes □ No | |

| Palliative care discussion with the patient done? | |

| □ Yes □ No | |

| Referral made? | |

| □ Yes □ No | |

| If yes, referral made to | |

| □ Duke palliative care | |

| □ Recommended to patient’s local oncologist for palliative care referral | |

| If screening score ≥ 5, and discussion did NOT take place and/or referral NOT made, why? | |

| □ Patient refused | |

| □ Provider did not agree: Attending/APP (please circle one) | |

| □ Other: ___________________________________________________________________________________________ |

References

[b1] Adelson, K., Pantilat, S. Z., Skye, E. P., Campbell, M. L., Epstein, A. S., Meier, D. E., & Knight, S. J. (2017). Effect of palliative care education on physician attitudes toward palliative care and willingness to refer. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(5), 517–523.

[b2] Albizu-Rivera, L., Smith, C. B., Deal, A. M., Fedorenko, C. R., Basch, E., & Mayer, D. K. (2016). National survey of palliative care utilization in comprehensive cancer centers. Journal of Oncology Practice, 12(7), 669–676.

[b3] Alcedo-Guardia, N., Labat, J. P., Blas-Boria, D., & Vivas-Mejia, P. E. (2016). Glioblastoma multiforme: Current perspectives in diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Management and Research, 8, 173–181.

[b4] Begum, N., Seow, H., Shafiq, M., Hui, D., Thorns, M., Haq, M., & Zimmermann, C. (2013). Impact of palliative care screening on referrals and service utilization in an outpatient cancer center. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 46(5), 718–726.

[b5] Davis, M. P., Temel, J. S., Balboni, T., & Glare, P. (2015). Integration of early palliative care for patients with cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(34), 4045–4052.

[b6] El-Jawahri, A., Traeger, L., Greer, J. A., VanDerWalde, A., Weeks, J. C., Jackson, V. A., & Temel, J. S. (2016). Effect of early palliative care vs usual care on depression among patients with advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncology, 2(12), 1634–1642.

[b7] Ferrell, B. R., Temel, J. S., Temin, S., Alesi, E. R., Balboni, T. A., Basch, E. M., & Zimmermann, C. (2017). Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35(1), 96–110.

[b8] Glare, P. A., & Chow, R. (2015). Validation of the palliative care needs assessment tool (PC-NAT) in an inpatient palliative care unit. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(1), 88–94.

[b9] Glare, P. A., Semple, R. J., Stabler, M. N., & Saltz, L. B. (2011). Palliative care in the outpatient oncology setting: A model program. Journal of Oncology Practice, 7(6), 365–370.

[b10] Grudzen, C. R., Richardson, L. D., Morrison, R. S., Cho, M. K., Hwang, U., Huynh, T., & Asch, S. M. (2016). The effect of palliative care consultation on hospital costs among patients with acute myocardial infarction: A randomized trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(8), 1117–1124.

[b11] Hui, D., Kim, S. H., Park, J. C., Zhang, Y., Strasser, F., Cherny, N. I., & Bruera, E. (2015). Integration of early palliative care into standard oncology care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26(8), 1596–1603.

[b12] Kumar, P., Woo, J., Thomas, R., Tan, G. S., Teng, C. L., & Malhotra, C. (2012). Barriers to palliative care referral in advanced cancer patients: A qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(11), 2805–2812.

[b13] Nakajima, N., & Abe, Y. (2016). Effects of early palliative care on quality of life and psychological distress in patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliative Medicine, 30(8), 727–738.

[b14] Ostrom, Q. T., Gittleman, H., Farahani, N., Rajaraman, P., McCarthy, M. C., Barnholtz-Sloan, J. S., & Patel, A. P. (2017). CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010–2014. Neuro-Oncology, 19(suppl_4), iv1–iv58.

[b15] Perrin, K. O., & Kazanowski, M. (2015). Palliative care: What every physician should know. The American Journal of Medicine, 128(1), 15–19.

[b16] Salins, N., Ramanjulu, R., Patra, L., Deodhar, J., & Muckaden, M. A. (2016). Impact of early palliative care in advanced cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Palliative Medicine, 30(7), 674–683.

[b17] Swarm, R., & Dans, L. (2018). NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 16(5), 575–584.

[b18] Temel, J. S., Greer, J. A., Muzikansky, A., Gallagher, E. R., Admane, S., Jackson, V. A., & Balboni, T. A. (2010). Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(8), 733–742.

[b19] Vanbutsele, G., Pardon, K., Van Belle, S., Bilsen, J., Deschepper, R., Vander Stichele, R., & Deliens, L. (2018). Effect of early integrated palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 19(9), e452–e464.

[b20] Walbert, T. (2014). Palliative care, hospice care, and end-of-life care in neuro-oncology practice: A literature review. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(11), 1278–1283.

[b21] Walbert, T., & Khan, M. (2014). Palliative care in neuro-oncology. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 14(12), 496.