Introduction

Family history (FH) is a crucial component of primary care, serving as an initial and often powerful step in identifying individuals at elevated risk for a variety of health conditions. A comprehensive family health assessment can illuminate patterns of disease within families, enabling early identification of those who could benefit from preventative measures, lifestyle adjustments, enhanced surveillance, or medical interventions guided by evidence-based practices [1, 2]. Despite the recognized benefits, family history tools are not consistently utilized to their full potential in primary care settings [3]. This underutilization is attributed to several barriers, including time constraints in busy primary care practices, lack of clinician training in FH collection and interpretation, patient-related inaccuracies in reported information, and variability in the standardization of FH tools themselves [4–7]. Furthermore, many FH tools currently in practice lack adequate validation [8–10].

To overcome these obstacles and effectively integrate family history into routine primary care, it is essential to employ tools that streamline FH collection, organize data effectively, demonstrate robust diagnostic performance, provide risk assessments (ideally algorithm-driven), and offer evidence-based recommendations. These tools must also be time-efficient for both patients and clinicians, with patient-reported acceptable completion times around 45 minutes [11]. Previous reviews have indicated that FH tools can indeed identify a significant proportion of individuals at increased risk who were previously unrecognized, and generally exhibit reasonable accuracy [1, 8, 13]. However, a critical gap remains in the systematic evaluation of these tools for clinical validity and utility within public health systems [7]. Currently, standardized guidelines for assessing the effectiveness of FH tools are lacking, although the ACCE (analytical validity, clinical validity, clinical utility, and ethical issues) framework, developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s Office of Public Health Genomics, has been recommended as a valuable evaluation framework [7, 14, 15].

This review aims to provide an updated evaluation of family history tools specifically designed for primary care. Building upon previous research, this article explores the currently available FH tools, focusing on their clinical performance and features relevant to practical implementation in primary healthcare settings. By examining their strengths and limitations, this review seeks to inform clinicians and healthcare systems about the potential and challenges of incorporating family assessment tools into routine primary care to improve patient risk stratification and ultimately, patient outcomes.

What are Family Assessment Tools in Primary Care?

Family Assessment Tools In Primary Care are structured instruments designed to gather and analyze patient family health history to identify individuals and families at increased risk for specific diseases or conditions. These tools move beyond simple questioning about family history, employing systematic methods to collect detailed information about relatives’ health status, age of onset of diseases, and sometimes lifestyle factors or ethnicity. The goal is to transform raw family history data into actionable insights that can inform clinical decision-making and personalize patient care within the primary care setting.

These tools vary significantly in their complexity and format. They can range from simple paper-based questionnaires to sophisticated computer-based systems integrated with electronic health records (EMRs). Some tools are generic, designed to screen for a wide range of common diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and various cancers, while others are disease-specific, focusing on risk assessment for a single condition, such as breast cancer or Lynch syndrome. Regardless of their format or scope, effective family assessment tools share the common objective of enhancing risk stratification in primary care, enabling clinicians to move from a reactive to a more proactive and preventive approach to patient health management. By systematically collecting and interpreting family health information, these tools aim to bridge the gap between genetic predisposition and practical clinical application in the everyday primary care environment.

Current Landscape of FH Tools in Primary Care

Types of Family History Tools

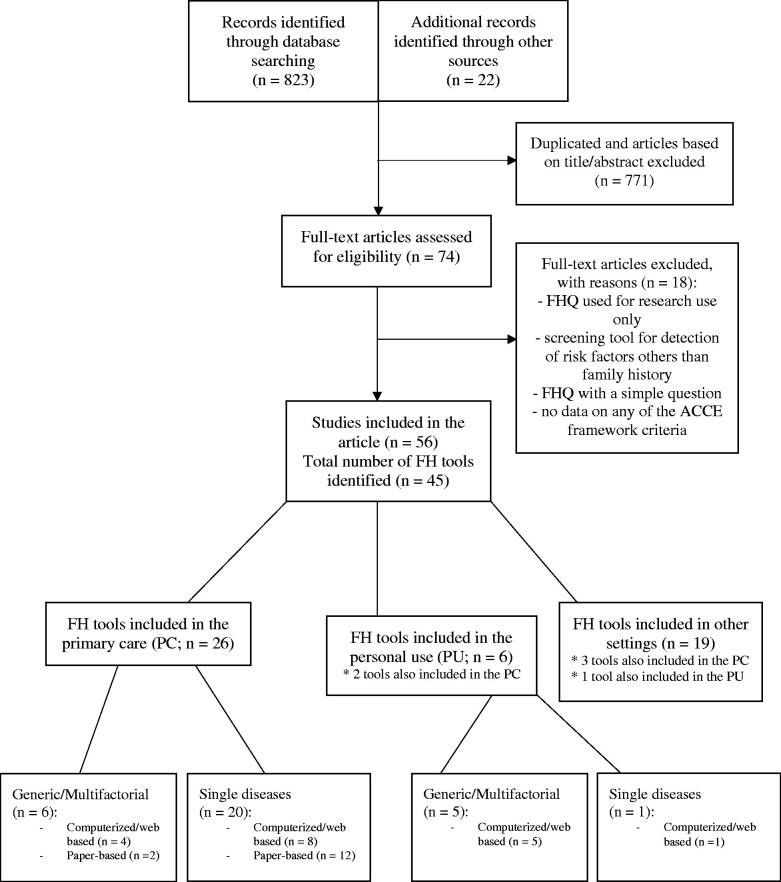

The review of family history tools available for primary care reveals a diverse landscape in terms of format and focus. Among the 26 tools identified as specifically designed for primary care, a notable split exists between generic and disease-specific tools. Six of these tools are classified as generic or multifactorial, designed to assess risk across a spectrum of conditions. Examples include tools like Family Healthware™, VICKY, MeTree, and Walter’s FHQ, which address risks for common diseases like breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancers, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and stroke [18–21]. Conversely, the majority, 20 out of 26 tools, are disease-specific, concentrating on evaluating family risk for a single disease or a related group of diseases. This category includes tools like RAGs, FHAT, GRACE, and GRAIDS, which are tailored for conditions such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and Lynch syndrome [24–28].

In terms of format, the tools are also divided between computer-based and paper-based instruments. Twelve of the reviewed primary care FH tools are computerized or web-based, offering potential advantages in terms of data management and integration. Fourteen tools remain paper-based, which may be simpler to implement in some clinical settings but lack the digital advantages of computerized systems. Interestingly, computerized tools generally tend to assess a broader range of diseases compared to their paper-based counterparts, suggesting a greater capacity for comprehensive risk assessment Supplementary Table S1. This variation in types and formats highlights the need for careful consideration when selecting an FH tool for primary care, ensuring it aligns with the specific needs and resources of the practice and patient population.

Key Features and Items in FH Tools

Family history tools in primary care are designed to systematically gather specific pieces of information to inform risk assessment. A core feature across all 26 reviewed tools is the inclusion of first-degree relatives (FDRs) – parents, siblings, and children – in the family health history assessment. These tools consistently inquire about the health status and age of disease onset for FDRs. Beyond first-degree relatives, many tools expand their scope to include more distant relatives to refine risk estimates. Specifically, 21 out of 26 tools also assess second-degree relatives (SDRs), such as grandparents, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, and half-siblings. A smaller subset, 12 out of 26 tools, extends the inquiry to third-degree relatives (TDRs), further broadening the scope of family health information collected.

Beyond the scope of relatives, some FH tools incorporate additional data points to enhance risk assessment. Eleven tools include questions about personal health history, which can provide context and refine individual risk estimates. Ethnicity, a factor that can influence the prevalence of certain genetic conditions, is considered in seven tools, primarily those focused on cancer risk assessment. Finally, reflecting the interplay of genetics and lifestyle in many diseases, two tools also assess health behaviors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption Table 3. This variability in the items included in FH tools underscores the importance of choosing a tool that not only aligns with the conditions being screened for but also captures the most relevant information for accurate risk stratification within the primary care context.

Alt text: Table 3 from the study, showcasing the items included in different family history tools for primary care. The table lists tool names and indicates whether they collect data on personal health history, health history of first, second, and third-degree relatives, age of disease onset in relatives, ethnicity, and health behavior.

Adoption in Primary Care Settings

Despite the availability of various family history tools, their integration and routine use in primary care settings remain limited. The original article highlights that while 26 tools were identified as designed for primary care, actual adoption and widespread implementation are not detailed. Anecdotal evidence and general observations within primary care practice suggest that family history collection often remains a manual and somewhat unstructured process, frequently relying on brief verbal questioning rather than standardized tools. Barriers to adoption include time constraints within typical primary care appointments, lack of seamless integration with existing electronic health record systems, and potentially a perceived lack of immediate clinical utility or clear guidance on how to act upon the collected family history information.

While some tools are designed for patient self-administration, which could mitigate the time burden on clinicians, the study notes that only one tool, MeTree, facilitates direct integration with EMR systems [20, 64]. This lack of interoperability is a significant hurdle for widespread adoption, as primary care practices increasingly rely on digital workflows and integrated systems. Furthermore, the variability in tool validation and the perceived complexity of interpreting family history data may also contribute to reluctance in adopting these tools in routine primary care practice. Moving forward, successful implementation of family assessment tools in primary care will likely require addressing these barriers through user-friendly tool design, streamlined EMR integration, clear clinical guidelines, and demonstrated improvements in patient outcomes and practice efficiency.

Evaluation of FH Tools: Performance and Limitations

The evaluation of family history tools for primary care extends beyond their features and design to encompass their actual clinical performance. This review assessed these tools based on several key criteria, including time to complete (TTC), patient administration, EMR system integration, risk assessment ability, evidence-based recommendations, and crucially, analytical and clinical validity, as well as clinical utility. These parameters are essential for determining the practical value and effectiveness of FH tools in routine primary care settings.

Time to Complete and Patient Administration

Efficiency is paramount in primary care, and the time required to complete a family history tool is a significant factor in its practicality. Information on time to complete (TTC) was reported for only eight of the reviewed tools. However, for those reporting TTC, the times were generally satisfactory, with a mean completion time of 17.9 minutes and a range from 81 seconds to 28 minutes. Six additional tools provided the number of items in the questionnaire (ranging from 3 to 9 items), offering some indication of questionnaire length and potentially completion time. The fact that most reported TTCs are under 30 minutes suggests that many of these tools are reasonably time-efficient for patient use.

In terms of administration, the majority of tools are designed for patient self-administration. All six generic/multifactorial tools are patient-administered [18–21, 23, 63]. Among the 20 disease-specific tools, 15 are designed for patient use, while five are intended for physician administration [24, 25, 28, 35, 42]. Patient self-administration is a significant advantage in primary care, as it offloads the initial data collection from clinicians, saving valuable appointment time. However, the accuracy of patient-reported family history and the need for clinician review and interpretation remain important considerations.

Integration with EMR Systems

A major factor influencing the seamless integration of family history tools into primary care workflows is their compatibility with Electronic Medical Record (EMR) systems. Disappointingly, among the 26 reviewed primary care FH tools, only one, MeTree, reported the capability to integrate FH reports directly into a patient’s EMR [20, 64]. The lack of EMR integration is a significant limitation for most currently available tools. Without direct integration, the data collected by FH tools may exist in isolation, requiring manual data entry or separate systems, which can be inefficient and increase the risk of errors. EMR integration is crucial for making family history data readily accessible within the patient’s medical record, facilitating clinical decision-making, tracking risk factors over time, and streamlining referrals or follow-up actions. The scarcity of EMR-integrated FH tools highlights a critical area for future development and improvement in this field.

Risk Assessment and Recommendations

A key function of family assessment tools is to provide risk assessment based on the collected family history data. Among the reviewed tools, 23 incorporate risk assessment capabilities, and 19 offer evidence-based management recommendations. However, the overlap between these features and primary care applicability is less extensive. Only five tools combine risk assessment and evidence-based recommendations specifically within the primary care context. This suggests that while many tools can identify individuals at increased risk, fewer provide direct guidance on subsequent clinical actions or management strategies within the primary care setting.

Interestingly, WICKY™, while not offering explicit risk assessment or recommendations, provides a printable PDF pedigree that clinicians can use for their interpretation and decision-making [19]. This highlights the spectrum of approaches in FH tools, ranging from tools that provide automated risk scores and recommendations to those that offer data visualization and leave risk interpretation and management decisions to the clinician. For optimal utility in primary care, tools that not only assess risk but also provide clear, evidence-based recommendations tailored to the primary care context are likely to be more valuable and easier to integrate into routine practice.

Clinical Validity and Utility: Strengths and Weaknesses

The clinical validity and utility of family history tools are paramount in determining their value in primary care. Clinical validity refers to how accurately a tool predicts disease risk, while clinical utility assesses the potential benefits and harms of using the tool in practice. The review evaluated these aspects using the ACCE framework, focusing on analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility (specifically benefits and psychological harm).

Analytical Validity: Analytical validity, which assesses how accurately the data is reported by the tool (e.g., accurate reporting of illnesses in relatives), was poorly reported across the reviewed studies. Only three tools reported on analytical validity [19, 40, 42], and in two of these, the assessment was deemed inadequate [40, 42]. WICKY™ showed acceptable analytical validity, but only for first-degree relatives [19]. This lack of analytical validity assessment is a significant concern, as it raises questions about the reliability of the family history data collected by these tools.

Clinical Validity: Clinical validity was more frequently reported, with 17 tools providing data on this aspect. Sensitivity, the ability of the tool to correctly identify individuals at high risk, was found to be good or acceptable for nine tools [21, 23, 25, 30, 34, 35, 38, 39, 43]. Specificity, the ability to correctly identify individuals at low risk, was reported as good or acceptable in four tools [21, 34, 35, 39] but was poor in another four [23, 25, 38, 43]. Agreement between FH tool results and a gold standard, often a pedigree interview with a genetic counselor, was commonly inadequately reported and assessed. When assessed, agreement was found to be adequately assessed in only five tools and acceptable in four [22, 26, 32, 38]. The mixed findings on sensitivity and specificity, and the limited data on agreement with gold standards, suggest that the clinical validity of many current FH tools remains a concern. Poor specificity, in particular, could lead to a higher rate of false positives, potentially resulting in unnecessary referrals and anxiety for patients.

Clinical Utility: Clinical utility, focusing on the benefits and adverse effects of using FH tools, was evaluated by examining benefits in risk identification, psychological impact, behavioral change, and adverse effects. Benefits were reported for 14 tools, with the primary benefit being the identification of individuals at increased risk. These tools successfully identified between 6.2% and 84.6% of individuals at high or moderate/increased risk [18, 20–22, 26, 32, 33, 35–37, 40, 41], and one tool identified 3.6% of individuals eligible for genetic testing [29]. Other reported benefits included increased reassurance, certainty about familial risk or referral needs, and raised awareness of disease risk [20, 30]. Importantly, studies generally suggested that FH collection did not lead to psychological distress [22, 27, 33], with only one study reporting transient anxiety symptoms that did not persist long-term [22]. Overall, the clinical utility of FH tools in terms of risk identification appears promising, with limited evidence of psychological harm.

Alt text: Figure 1 from the study, illustrating the selection process of included studies for the systematic review of family history tools. The flowchart visually represents the number of articles identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and finally included in the review, according to PRISMA guidelines.

Discussion

Main Findings and Implications

This review provides a comprehensive overview of family history tools designed for primary care, evaluating their characteristics, usability, clinical performance, and potential for EMR integration. The findings highlight that while numerous FH tools are available, their routine clinical or personal use is not yet fully supported by robust evidence of validation and seamless integration. Tools designed for primary care are frequently disease-specific, particularly focused on cancer risk, and are often paper-based. While completion times are generally acceptable, the crucial aspects of analytical and clinical validity are often inadequately assessed and reported.

The lack of rigorous validation is a major concern. Analytical validity, essential for ensuring data accuracy, is seldom evaluated. Clinical validity, while more frequently assessed, often shows mixed results, with acceptable sensitivity but frequently poor specificity. This raises the possibility of over-referral and increased patient anxiety. Despite these limitations, the potential benefits of FH tools in identifying at-risk individuals are evident, with studies showing successful identification of a significant proportion of high-risk individuals without causing significant psychological distress.

Comparison with Existing Literature

The findings of this review align with previous research, such as Reid et al. [8], which also highlighted the potential benefits of FH tools in risk identification and increasing risk perception. Consistent with earlier reviews [9, 13], this study also encountered challenges in comparing tools due to heterogeneity in format, approach, and the range of diseases assessed. The conclusion remains similar to reviews conducted nearly a decade prior: recommending a specific FH tool for widespread implementation is still difficult due to the limitations in validation and standardization.

Despite the development of new tools and updates to existing ones since 2014 [19, 20, 31, 41–43, 45–47], and the emergence of MeTree with EMR integration [20], a fully validated FH tool that comprehensively addresses analytical and clinical validity, provides algorithm-based risk assessment, offers evidence-based recommendations, and ensures adequate time efficiency remains elusive. The “recommended tools” list derived from this review Table 5 differs from previous recommendations [9], emphasizing the evolving nature of FH tool development and the ongoing need for rigorous evaluation. The consensus, echoing Ginsburg [1], remains that ideal FH tools should be patient-completed, preferably web-based for EMR compatibility, completed within 30 minutes, and include data on first and second-degree relatives, personal information, and point-of-care recommendations.

Methodological Considerations and Future Directions

The limitations of this review, primarily the inconsistent and often inadequate assessment of analytical and clinical validity in the included studies, underscore the need for more rigorous validation methodologies in future FH tool development. Obtaining data from medical records and verifying patient-reported family history are crucial steps to enhance the accuracy of validity assessments. Future research should focus on evaluating FH tools’ capacity to identify specific high-risk groups and track the uptake of genetic counseling referrals following FH tool-based risk assessments.

Despite the limitations, the ACCE framework remains a valuable, albeit imperfect, tool for evaluating FH tools. Moving forward, a standardized approach to validation, incorporating analytical validity, robust clinical validity measures, and comprehensive clinical utility assessments, including ethical and legal implications, is essential. Future FH tool development should prioritize EMR integration, patient-centered design, and clear, actionable recommendations for primary care clinicians.

Conclusion

Family history tools hold significant promise for improving risk stratification and preventive care in primary care settings. However, the current generation of tools exhibits limitations in clinical performance, particularly in terms of specificity and comprehensive validation, and lacks seamless integration with EMR systems. While many tools are designed for patient self-administration, further development and rigorous validation are needed to fully realize their potential and facilitate their widespread and effective implementation in routine primary care practice. Future efforts should focus on developing and validating user-friendly, EMR-integrated FH tools that provide accurate risk assessments and clear, evidence-based recommendations to empower primary care clinicians to effectively utilize family history for improved patient care.