Objective:

The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) set the stage for standardized patient functional data collection across various post-acute care settings. This initiative brought Section GG to the forefront as a crucial tool. This article delves into a comparative analysis of clinician-observed scores using Section GG and the Functional Independent Measure® (FIM), specifically within inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs). Our goal is to highlight the significance of Section GG in modern healthcare, addressing the question of its purpose and impact as a vital care assessment tool.

Design:

This study is a secondary analysis of the 2017 Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSMR) national dataset. Within IRFs, clinicians evaluated patients using both Section GG and FIM at the point of admission and discharge. We focused on seven self-care and six transfer items within Section GG that conceptually mirrored items in the FIM assessment. Our analytical approach included examining score distributions, Bland-Altman plots, correlation analyses (using Pearson coefficients), and agreement analyses (kappa and weighted kappa statistics) for each item pair.

Setting and Participants:

The study population comprised 408,491 patients admitted to UDSMR-affiliated IRFs. These patients were admitted with primary impairments in one of five categories: stroke, brain dysfunction, neurologic conditions, orthopedic disorders, or debility.

Measures:

The core measures for this study were the Section GG and FIM assessments.

Results:

Our analysis revealed a trend where patients received higher functional independence scores when assessed with Section GG compared to FIM. However, the distribution of change scores and the order of scores across different impairment groups showed similarities between the two assessment tools. Total scores from Section GG exhibited strong positive correlations with total FIM scores (self-care: r=0.87 and 0.95; transfer: r=0.82 and 0.90 at admission and discharge, respectively). Ranking agreements, when compared to total FIM scores, ranged from weak to moderate (self-care: kappa= 0.49 and 0.60; transfers: kappa= 0.43 and 0.52 at admission and discharge, respectively). Agreements were notably lower for patients with reduced functional abilities at admission and for higher-functioning patients when considering change scores.

Conclusions and Implications:

The response patterns between Section GG and FIM demonstrated overall consistency across various impairments. Nevertheless, we identified variations in score distributions and ranking agreement. Moving forward, it is crucial for research to focus on how to effectively utilize GG codes to ensure consistent care quality, optimize patient outcomes, and maintain equitable reimbursement practices within post-acute care settings. Understanding these nuances is key to leveraging Section GG to its full potential as a valuable tool in patient care.

Keywords: Subacute Care, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Health Services Administration, Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care, Mobility, Self-Care, Critical Care Outcomes

Brief Summary:

This study establishes baseline evidence by evaluating response patterns from the IMPACT Act’s mandatory standardized functional data sets. This foundation is essential for refining quality reporting and ensuring effective care delivery, outcome measurement, and unbiased reimbursement models across the spectrum of post-acute care.

Introduction

The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) is reshaping the landscape of post-acute care by standardizing the evaluation and reimbursement of functional status, care processes, and services.1 Addressing the inconsistencies arising from varied functional assessments across post-acute settings, the IMPACT Act mandates the use of standardized patient assessment data elements (SPADEs) throughout the post-acute care continuum.1–4 Section GG emerged as a key component of SPADEs, designed to consistently measure functional abilities and track patient goals across inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRF), skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care hospitals.2,3

Since the inception of the IRF prospective payment system (IRF-PPS) in 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had already integrated 11 items from the Functional Independence Measure® (FIM) into the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI).5 These FIM items served to quantify patients’ performance in essential daily activities and the level of assistance required (care burden).6 While the IRF-PAI encompasses more than just FIM items, for simplicity, this paper will refer to the functional items previously used in IRF-PAI as FIM, and the newly standardized functional items within IRF-PAI as Section GG. CMS mandated the adoption of Section GG starting in October 2016, fully replacing the FIM functional items by October 2019.6 However, direct comparative data between Section GG and FIM remains limited. A 2019 analysis of FY 2017 Medicare data indicated a minor difference in cost prediction models. These models used either CMGs based on the original IRF-PPS (FIM items) or CMGs based on SPADEs (GG items).7

In June 2019, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) voiced concerns regarding the reliability of reported functional data from post-acute care providers.8 IRFs began the dual collection of Section GG and FIM functional data in 2016 as part of the IRF Quality Reporting Program.9 This three-year period of concurrent data collection at IRFs provides a unique opportunity to examine the transitional impact on how clinicians and facilities evaluate and report functional outcomes. Our study leverages this unique 2017 dataset, featuring simultaneous Section GG and FIM data from IRFs, to analyze response patterns across nearly 900 U.S. IRFs.

This study is structured around three primary aims: 1) to develop an algorithm for identifying scoring discrepancies between Section GG and FIM; 2) to characterize the distributions of standardized functional outcomes at admission, discharge, and functional change across different impairment conditions; and 3) to compare and contrast clinician-observed scores in Section GG and FIM for the same IRF patient.

Methods

Data Source

Our data was sourced from the 2017 Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSMR®). UDSMR maintains the largest non-governmental database for inpatient medical rehabilitation outcomes in the U.S., covering approximately 70% of IRFs, including both freestanding inpatient rehabilitation hospitals and acute hospital-based rehabilitation units. The study received approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board, and a Data Use Agreement with UDSMR was secured.

Study Population

The study focused on patients whose primary admission diagnosis fell into one of the following categories: stroke, brain dysfunction, neurologic condition, orthopedic disorders, and debility. These conditions collectively represent over 90% of our IRF patient cohort. Each patient underwent assessments using both Section GG and FIM items at admission and/or discharge (Suppl. Table 1).

Developing an Algorithm to Identify Scoring Discrepancy

To address the data fidelity concerns raised by MedPAC, we designed an algorithm to detect ratings between Section GG and FIM that were inconsistent or clinically implausible (Table 1). This algorithm was informed by the scoring guidelines from the IRF-PAI manuals11 and the clinical expertise of our research team. For example, we deemed it clinically implausible if a patient received a score of 7 (complete independence) on FIM but a score of 1 (complete dependence) on Section GG for equivalent items. The first and second authors collaborated, applying clinical judgment to reach a consensus on which scoring combinations were definitively implausible (Table 1). Suppl. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the rating scale structures for Section GG and FIM Items.

Table 1. Algorithm to Determine Consistent and Implausible Ratings between Section GG and FIM.

| Functional Independence Measure Rating Scale | Section GG Rating Scale | O= Consistent X= Implausible |

|---|---|---|

| 7 Complete Independence | 6 Independent | O |

| 5 Set up clean up | O | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | X | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | X | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | X | |

| 1 Dependent | X | |

| 6 Modified Independence | 6 Independent | O |

| 5 Set up clean up | O | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | X | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | X | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | X | |

| 1 Dependent | X | |

| 5 Supervision | 6 Independent | X |

| 5 Set up clean up | O | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | O | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | X | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | X | |

| 1 Dependent | X | |

| 4 Minimal Assistance (>75%) | 6 Independent | X |

| 5 Set up clean up | X | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | O | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | O | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | X | |

| 1 Dependent | X | |

| 3 Moderate Assistance (51-75%) | 6 Independent | X |

| 5 Set up clean up | X | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | O | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | O | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | X | |

| 1 Dependent | X | |

| 2 Maximal Assistance (26-50%) | 6 Independent | X |

| 5 Set up clean up | X | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | X | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | O | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | O | |

| 1 Dependent | O | |

| 1 Total Assistance (0-25%) | 6 Independent | X |

| 5 Set up clean up | X | |

| 4 Supervision or touching | X | |

| 3 Partial/Moderate | X | |

| 2 Substantial/maximal | O | |

| 1 Dependent | O |

Abbreviations: FIM=Functional Independence Measure® scores; Section GG: functional ability scores in the standardized patient assessment data elements (SPADEs) assessment instrument. Please refer to Methods for details regarding how this algorithm was developed.

Standardized Functional Data: Section GG

Section GG encompasses two primary domains: self-care and mobility, with seven and 17 items respectively (Suppl. Table 3). For a fair comparison with FIM scores, we selected six transfer items from Section GG (roll left and right, sit to lying, lying to sit on side of bed, sit to stand, chair/bed-to-chair transfer, and toilet transfer) that aligned with three transfer items in FIM (bed/chair/wheelchair transfer, toilet transfer, and tub/shower transfer). Where direct item correspondence was lacking, we selected the most conceptually similar items (Suppl. Table 3).

Total scores for self-care and transfer were calculated for both Section GG and FIM at admission and discharge. Change scores were derived by subtracting the admission score from the discharge score. Total GG raw scores range from 7-42 for self-care and 6-36 for transfer. Total FIM scores range from 6-42 for self-care and 3-21 for transfer. To account for differences in rating scales (Section GG: 1-6; FIM: 1-7) (Suppl. Table 2), we recalibrated scores to a 0-100% ratio for direct comparison. Each total score was adjusted by subtracting the mean domain score and then dividing by the domain score range. These recalibrated total scores were then divided into quartiles based on their distribution to assess ranking agreement.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were stratified by impairment for descriptive analyses. Following CMS guidelines,12 missing FIM scores or scores of ‘0’ (activity not occurring) were treated as a score of 1 (lowest function). To enhance data fidelity, we excluded patients who had more than 3 items with implausible ratings within a single domain, as determined by our algorithm (Table 1). To ensure comprehensive domain-level comparisons, patients with any missing data (Step 2, Suppl. Table 1) were also excluded. We created separate subsamples for each domain (self-care and transfer) and evaluation time point (admission and discharge) for correlation and agreement analyses. Pearson coefficients were used to assess the correlations between recalibrated total scores of Section GG and FIM, using Mukaka’s criteria13 (0.3-0.5: low, 0.5-0.7: moderate, 0.7-0.9: high). Given that correlations alone do not capture score differences, Cohen’s kappa/weighted kappa criteria14 (0.4-0.59: weak, 0.6-0.79: moderate, 0.8-0.9: strong) were used to evaluate ranking agreement levels. Bland-Altman plots were employed to further investigate whether lower agreement levels were associated with lower, middle, or higher ability ranges.15

Results

Demographics

Table 2 summarizes the demographic characteristics of 408,491 patients who received inpatient rehabilitation services between January and December 2017, as recorded in the UDSMR. The average age was 70.0 years (SD 14.4), with a majority being non-Hispanic white (77.1%), female (53.2%), married (47.8%), and living with family/relatives prior to acute care hospitalization (67.8%). The mean Elixhauser comorbidity index was 3.8 (SD 2.0). Stroke was the most common primary rehabilitation impairment (29.8%), followed by orthopedic disorders (27.3%), neurologic conditions (17.4%), brain dysfunction (14.5%), and debility (11.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics by Impairment Groups (N=408,491).

| All(n=408,491) | Stroke(n=121,640) | Brain Dysfunction(n=59,184) | Neurologic Condition(n=70,886) | Orthopedic Disorders(n=111,581) | Debility(n=45,200) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at admission – CMS Calendar (years) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 70.0 (14.4) | 69.1 (13.3) | 66.7 (16.9) | 69.5 (14.3) | 71.9 (14.1) | 72.6 (13.3) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 72 (62, 81) | 70 (60, 79) | 70 (58, 79) | 72 (62, 80) | 74 (64, 83) | 75 (65, 83) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 191358 (46.9) | 63206 (52.0) | 32415 (54.8) | 34447 (48.6) | 39598 (35.5) | 21692 (48) |

| Female | 217062 (53.2) | 58404 (48.0) | 26757 (45.2) | 36434 (51.4) | 71967 (64.5) | 23500 (52) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 315002 (77.1) | 83985 (69.0) | 45439 (76.8) | 56715 (80.0) | 92505 (82.9) | 36358 (80.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 47880 (11.7) | 20451 (16.8) | 6260 (10.6) | 8042 (11.3) | 8116 (7.3) | 5011 (11.1) |

| Hispanic | 21103 (5.2) | 7298 (6) | 3326 (5.6) | 3538 (5.0) | 5177 (4.6) | 1764 (4.0) |

| Others | 24506 (6) | 9906 (8.1) | 4159 (7.0) | 2591 (3.7) | 5783 (5.2) | 2067 (4.6) |

| BMI, n (%) | ||||||

| Underweight | 19971 (5.0) | 5055 (4.2) | 3461 (5.9) | 3571 (5.1) | 5457 (5.0) | 2427 (5.4) |

| Normal weight | 120403 (29.9) | 35101 (29.3) | 20545 (35.2) | 19612 (28.0) | 32240 (29.3) | 12905 (28.9) |

| Overweight | 118677 (29.5) | 39002 (32.5) | 17549 (30.1) | 19274 (27.5) | 30699 (27.9) | 12153 (27.2) |

| Obesity | 143976 (35.7) | 40700 (44.0) | 16789 (28.8) | 27524 (39.3) | 41788 (37.9) | 17175 (38.5) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||||

| Never Married | 70747 (17.8) | 21837 (18.5) | 12155 (21.1) | 12260 (17.7) | 17208 (15.9) | 7287 (16.6) |

| Married | 189662 (47.8) | 58953 (50.0) | 28971 (50.4) | 33580 (48.6) | 48677 (44.9) | 19481 (44.3) |

| Widowed | 91701 (23.1) | 23164 (19.6) | 10351 (18.0) | 15320 (22.2) | 30667 (28.3) | 12199 (27.7) |

| Separated | 4161 (1.1) | 1522 (1.3) | 547 (1.0) | 699 (1.0) | 971 (0.9) | 422 (1.0) |

| Divorced | 40839 (10.3) | 12490 (10.6) | 5461 (9.5) | 7271 (10.5) | 11019 (10.2) | 4598 (10.5) |

| Comorbidity Tier, n (%) | ||||||

| No cost | 195044 (47.8) | 66933 (55.0) | 21813 (36.9) | 25274 (35.7) | 66339 (59.5) | 14685 (32.5) |

| Lowest cost | 20278 (5.0) | 49784 (40.9) | 3598 (6.1) | 6060 (8.6) | 2785 (2.5) | 3966 (8.8) |

| Medium cost | 33368 (8.2) | 1054 (0.9) | 12796 (21.6) | 9616 (13.6) | 5124 (4.6) | 4778 (10.6) |

| Highest cost | 159801 (39.1) | 3869 (3.2) | 20977 (35.4) | 29936 (42.2) | 37333 (33.5) | 21771 (48.2) |

| Region, n (%) | ||||||

| CT, RI, MA, ME, NH, VT | 20747 (5.1) | 6627 (5.5) | 2761 (4.7) | 2611 (3.7) | 6188 (5.6) | 2560 (5.7) |

| NY, NJ | 25543 (6.3) | 9064 (7.5) | 3698 (6.3) | 2969 (4.2) | 7443 (6.7) | 2369 (5.2) |

| PA, WV, VA, DC, MD, DE | 52267 (12.8) | 14560 (12.0) | 7022 (11.9) | 10566 (14.9) | 14837 (13.3) | 5282 (11.7) |

| KY, TN, MS, AL, GA, SC, NC, FL | 87458 (21.4) | 24263 (20.0) | 11655 (19.7) | 15730 (22.2) | 25124 (22.5) | 10686 (23.6) |

| MN, WI, MI, IL, IN, OH | 55224 (13.5) | 18586 (15.3) | 9712 (16.4) | 9467 (13.4) | 11028 (9.9) | 6431 (14.2) |

| NM, OK, AR, TX, LA | 83305 (20.4) | 19722 (16.2) | 10113 (17.1) | 17479 (24.7) | 25966 (23.3) | 10025 (22.2) |

| NE, IA, KS, MO | 20837 (5.1) | 6818 (5.6) | 3319 (5.6) | 3050 (4.3) | 5063 (4.5) | 2587 (5.7) |

| MT, ND, WY, SD, UT, CO | 12770 (3.1) | 3975 (3.3) | 2316 (3.9) | 1589 (2.2) | 3681 (3.3) | 1209 (2.7) |

| NV, CA, AZ | 43770 (10.7) | 14375 (11.8) | 7367 (12.5) | 6985 (9.9) | 11410 (10.2) | 3633 (8.0) |

| WA, OR, ID | 6570 (1.6) | 3650 (3) | 1221 (2.1) | 440 (0.6) | 841 (0.8) | 418 (0.9) |

| Pre-hospital Living With, n (%) | ||||||

| Alone | 110955 (27.5) | 30093 (25.0) | 13426 (23.0) | 18449 (26.5) | 35401 (32.0) | 13586 (30.6) |

| Family/Relative | 273379 (67.8) | 84697 (70.5) | 41875 (71.7) | 47874 (68.8) | 70228 (63.6) | 28705 (64.7) |

| Friends | 7902 (2.0) | 2779 (2.3) | 1427 (2.4) | 1200 (1.7) | 1800 (1.6) | 696 (1.6) |

| Attendant | 5004 (1.2) | 1023 (0.9) | 747 (1.3) | 1028 (1.5) | 1460 (1.3) | 746 (1.7) |

| Other | 5858 (1.5) | 1604 (1.3) | 943 (1.6) | 1079 (1.6) | 1585 (1.4) | 647 (1.5) |

| Discharge Living With, n (%) | ||||||

| Alone | 11135 (9.6) | 2877 (7.1) | 1311 (6.9) | 1886 (11.2) | 3633 (12.1) | 1428 (14.0) |

| Family/Relatives | 90655 (77.7) | 33237 (82.1) | 15537 (81.2) | 12145 (72.2) | 22345 (74.5) | 7391 (72.3) |

| Friends | 2649 (2.7) | 978 (2.4) | 483 (2.5) | 319 (1.9) | 679 (2.3) | 190 (1.9) |

| Attendant | 1842 (1.6) | 589 (1.5) | 344 (1.8) | 251 (1.5) | 438 (1.5) | 220 (2.2) |

| Othersa | 10374 (8.9) | 2795 (6.9) | 1466 (7.7) | 2214 (13.2) | 2911 (9.7) | 988 (9.7) |

| Pre-hospital Living Setting, n (%) | ||||||

| Homeb | 403098 (98.7) | 120196 (98.8) | 58418 (98.7) | 69630 (98.2) | 110474 (99.0) | 44380 (98.2) |

| Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) | 1265 (0.3) | 372 (0.3) | 203 (0.3) | 267 (0.4) | 233 (0.2) | 190 (0.4) |

| Home under care of organized home health service organization | 266 (0.1) | 116 (0.1) | 25 (0.0) | 71 (0.1) | 35 (0.03) | 19 (0.0) |

| Othersa | 3862 (1.0) | 956 (0.8) | 538 (0.9) | 918 (1.3) | 839 (0.8) | 611 (1.4) |

| Admitted to Rehab From, n (%) | ||||||

| Homeb | 13768 (3.4) | 2888 (2.4) | 1156 (2.0) | 4881 (6.9) | 2843 (2.6) | 2000 (4.4) |

| Short-term General Hospital | 381965 (93.5) | 115467 (94.9) | 56233 (95.0) | 62044 (87.5) | 106631 (95.6) | 41590 (92.0) |

| Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) | 3980 (1.0) | 1473 (1.2) | 483 (0.8) | 789 (1.1) | 909 (0.8) | 326 (0.7) |

| Othersa | 8778 (2.2) | 1812 (1.5) | 1312 (2.2) | 3172 (4.5) | 1198 (1.2) | 1284 (2.8) |

| Discharge Setting, n (%) | ||||||

| Homeb | 116655 (28.6) | 40476 (33.3) | 19141 (32.3) | 16815 (23.7) | 30006 (26.9) | 10217 (22.6) |

| Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) | 51579 (12.6) | 20619 (17.0) | 6572 (11.1) | 6753 (9.5) | 13645 (12.2) | 3990 (8.8) |

| Home under care of organized home health service organization | 386 (0.1) | 168 (0.1) | 68 (0.1) | 42 (0.1) | 72 (0.1) | 36 (0.1) |

| Othersa | 239871 (58.7) | 60377 (49.6) | 33403 (56.4) | 47276 (66.7) | 67858 (60.8) | 30957 (68.5) |

| Total Length of Stay, R&D Calc. | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 13.0 (7.3) | 15.2 (8.7) | 13.1 (8.8) | 12.5 (6.6) | 11.7 (4.9) | 11.3 (5.4) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 12 (9, 16) | 14 (9, 20) | 12 (8, 16) | 12 (9, 15) | 12 (8, 15) | 11 (8, 14) |

| Actual Net Length of Stay | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 13 (7.3) | 15.2 (8.7) | 13.1 (8.8) | 12.5 (6.6) | 11.7 (4.9) | 11.3 (5.4) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 12 (9, 16) | 14 (9, 20) | 12 (8, 16) | 12 (9, 15) | 12 (8, 15) | 11 (8, 14) |

| Expected Net Length of Stay | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.3 (4.6) | 17.9 (5.7) | 15.3 (4.4) | 14.7 (3.7) | 13.7 (3.1) | 13.5 (3.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 15 (12, 17) | 17 (14, 24) | 14 (12, 18) | 15 (13, 17) | 14 (11, 16) | 13 (12, 16) |

| Number of Elixhauser comorbidity | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (2.0) | 4.2 (1.9) | 3.8 (2.0) | 4.1 (2.1) | 3.2 (1.9) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (2, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 6) |

All demographic characteristics were significantly different by impairment groups (p<0.001).

a. ‘Others’ included short-term general hospital, hospice (home and institutional facility), another inpatient rehabilitation facility, long-term care hospital (LTCH).

b. ‘Home’ included private home/apartment, board/care, assisted living, group home, transitional living.

Abbreviations: SC: Self-Care; Trans: Transfer.

Using Algorithm to identify Scoring Discrepancy between Assessments

Suppl. Table 4 presents the percentage of implausible scores found between Section GG and FIM. Self-care items showed greater scoring consistency among clinicians compared to transfer items. Within self-care and transfer domains, Section GG lower-body dressing (89.1%) and toilet transfer (88.7%) were the most consistently scored items, while oral hygiene (72.7%) and roll left and right (58.3%) showed the least consistency. The application of our algorithm led to improved correlations and agreements, particularly for transfer change scores, especially within the orthopedic disorders group (Table 3, Suppl. Table 6).

Table 3. Correlation and Ranking Agreement between Section GG and FIM by Impairment (after Removing Discordant Scores).

| All | Stroke | Brain Dysfunction | Neurologic condition | Orthopedic Disorders | Debility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | n | Corr., (95 CI) | n | Corr., (95 CI) | n | Corr., (95 CI) |

| Admission Score | ||||||

| Self-Care | 291,836 | 0.87 (0.87, 0.87) | 87,392 | 0.90 (0.90, 0.90) | 41,055 | 0.89 (0.89, 0.89) |

| Transfer | 258,234 | 0.82 (0.81, 0.82) | 79,284 | 0.85 (0.85, 0.85) | 37,876 | 0.82 (0.82, 0.82) |

| Discharge Score | ||||||

| Self-Care | 348,357 | 0.95 (0.95, 0.95) | 103,322 | 0.95 (0.95, 0.96) | 49,200 | 0.95 (0.95, 0.95) |

| Transfer | 291,424 | 0.90 (0.90, 0.90) | 88,736 | 0.92 (0.92, 0.92) | 41,718 | 0.90 (0.90, 0.90) |

| Change Score | ||||||

| Self-Care | 265,572 | 0.80 (0.79, 0.80) | 79,873 | 0.80 (0.80, 0.81) | 36,994 | 0.82 (0.82, 0.82) |

| Transfer | 200,369 | 0.73 (0.73, 0.74) | 62,570 | 0.73 (0.72, 0.73) | 29,142 | 0.73 (0.72, 0.73) |

| Agreement | n | Kappa (95 CI) Weighted Kappa (95 CI) | n | Kappa (95 CI) Weighted Kappa (95 CI) | n | Kappa (95 CI) Weighted Kappa (95 CI) |

| Admission Score | ||||||

| Self-Care | 291,836 | 0.49 (0.49, 0.50) 0.68 (0.68, 0.68) | 87,392 | 0.56 (0.55, 0.56) 0.73 (0.72, 0.73) | 41,055 | 0.54 (0.53, 0.54) 0.71 (0.70, 0.71) |

| Transfer | 258,234 | 0.43 (0.43, 0.43) 0.62 (0.62, 0.62) | 79,284 | 0.48 (0.48, 0.49) 0.67 (0.67, 0.68) | 37,876 | 0.43 (0.42, 0.43) 0.61 (0.61, 0.62) |

| Discharge Score | ||||||

| Self-Care | 348,357 | 0.60 (0.60, 0.60) 0.76 (0.76, 0.76) | 103,322 | 0.68 (0.68, 0.69) 0.81 (0.81, 0.82) | 49,200 | 0.61 (0.60, 0.61) 0.76 (0.76, 0.77) |

| Transfer | 291,424 | 0.52 (0.51, 0.52) 0.70 (0.70, 0.70) | 88,736 | 0.58 (0.57, 0.58) 0.74 (0.74, 0.74) | 41,718 | 0.55 (0.55, 0.56) 0.72 (0.72, 0.72) |

| Change Score | ||||||

| Self-Care | 265,572 | 0.40 (0.40, 0.40) 0.58 (0.58, 0.58) | 79,873 | 0.41 (0.40, 0.41) 0.58 (0.58, 0.59) | 36,994 | 0.42 (0.41, 0.43) 0.59 (0.59, 0.60) |

| Transfer | 200,369 | 0.32 (0.31, 0.32) 0.49 (0.48, 0.49) | 62,570 | 0.32 (0.32, 0.33) 0.50 (0.49, 0.50) | 29,142 | 0.31 (0.30, 0.32) 0.49 (0.48, 0.49) |

Abbreviations: Corr.= Correlation.

a: Created by using tertile.

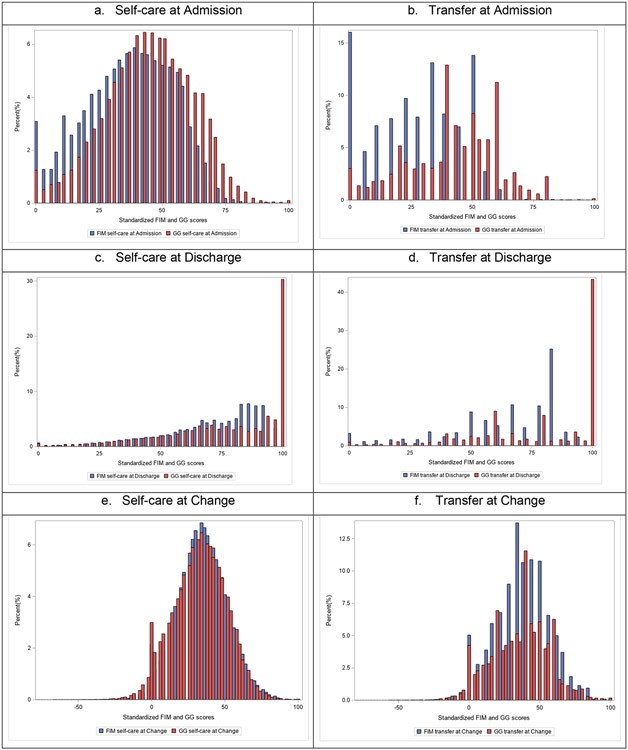

Recalibrated Total Score Distributions

The distributions of recalibrated (0-100%) total scores for self-care and transfer, using both Section GG and FIM, are shown for admission, discharge, and change scores in (Figure 1). Detailed score distributions, including medians, means, SD, skewness, and kurtosis for Section GG and FIM, are available in Suppl. Table 5. At admission, both self-care and transfer scores displayed relatively normal distributions, but FIM scores showed a heavier tail towards the lower-functioning end, suggesting it may be less sensitive in discriminating among patients with lower functional levels. For self-care at discharge, both assessments resulted in non-normal distributions, with Section GG exhibiting a clear ceiling effect. In transfer assessments at discharge, both tools produced non-normal distributions with pronounced “ceiling effects,” although the FIM ceiling was around 80. Self-care change score distributions were nearly identical for both assessments, although Section GG identified more patients experiencing a decline in self-care performance. Transfer change score distributions were relatively normal and similar, with FIM change scores showing a more peaked distribution. Both assessments were capable of detecting some degree of decline in transfer performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Section GG and FIM Recalibrated Score Distributions (0-100%) (Top: Admission, Middle: Discharge, Bottom: Change; Red: Section GG; Blue: FIM).

Figure 1 illustrates the recalibrated self-care and mobility score distributions for Section GG and FIM at admission, discharge, and the change between admission and discharge (discharge – admission). Red lines represent Section GG, and blue lines represent FIM. Abbreviations: FIM: Functional Independence Measure. Alt Text: Figure 1 displays histograms comparing score distributions of Section GG (red) and FIM (blue) for self-care and mobility at admission, discharge, and change scores, illustrating distributional differences between the two functional assessment tools.

Recalibrated Scores by Impairment

Across different impairments, the score variations between Section GG and FIM were more pronounced at admission compared to discharge and change scores (Suppl. Figure 1). Generally, the scores from both assessments across impairment groups aligned with clinical expectations. For instance, patients with orthopedic conditions were the most functionally independent in self-care but the least in transfer at admission, relative to other impairment groups. Similar patterns were observed for both Section GG and FIM across impairments. For example, patients with debility scored highest in self-care at admission, followed by those with orthopedic disorders, brain dysfunction, neurological conditions, and stroke, across both assessments (Suppl. Figure 1, self-care panel). Patients showed improved independence at discharge compared to admission, irrespective of the assessment tool used or the type of impairment. Section GG demonstrated a wider score range than FIM across impairments (e.g., admission self-care in stroke: range 31-42 in Section GG vs. 31-34 in FIM), but the score ranges for change scores were comparable (Suppl. Figure 1).

Correlation & Ranking Agreement

Using recalibrated total scores, Section GG showed moderate to strong correlations with FIM at both admission and discharge (>0.8) and for change scores (ranging from 0.70-0.82). Discharge scores consistently exhibited stronger correlations than admission scores, regardless of the functional domain or impairment (Table 3).

Section GG demonstrated weak to moderate agreement in ranking with FIM; the lowest agreement was observed in transfer change scores (weighted kappa range 0.45-59). Patients with stroke showed the strongest correlations and agreements, followed by those with brain dysfunction and neurological conditions (Table 3).

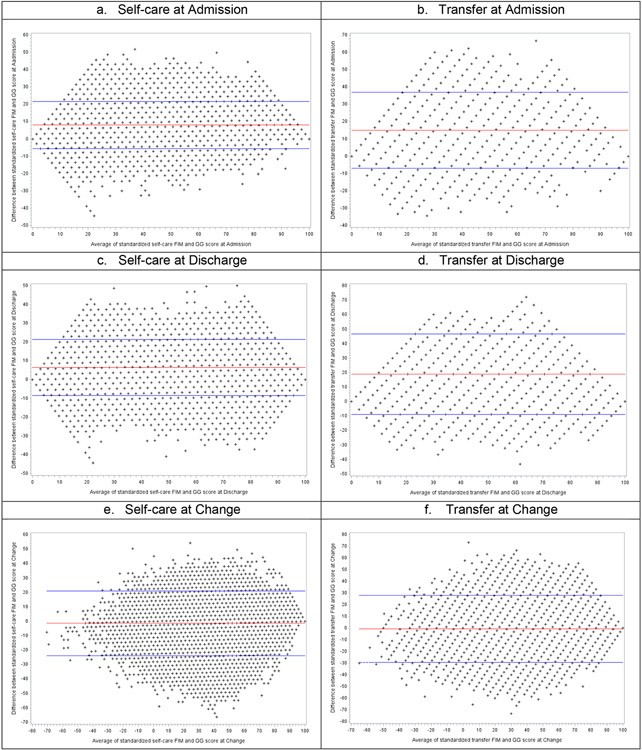

Bland-Altman Plots of Recalibrated Total Scores

Bland-Altman plots were used to assess bias between the mean differences of the two assessments and to estimate 95% agreement intervals (± 2 SD).15,16 The means of the Bland-Altman plots were not zero, indicating a tendency for patients to score higher (more functionally independent) on Section GG than on FIM. Patients with lower average ability levels showed reduced agreement between the two assessments at admission (Figure 2, admission plots: lower left below the lower 95% CI), especially when FIM scores were higher. Similarly, patients with higher average ability levels had lower agreement for change scores (Figure 2, change score plots: lower right below the lower 95% CI), particularly those with larger change scores and higher FIM scores.

Figure 2. Bland-Altman Plot between Section GG and FIM Recalibrated Scores (0-100%) (Top: Admission, Middle: Discharge, Bottom: Change).

Figure 2 shows Bland-Altman plots comparing recalibrated self-care and mobility scores from Section GG and FIM at admission, discharge, and change (discharge – admission). The x-axis represents the average of the two measures ([Section GG+ FIM]/2), and the y-axis shows the difference (Section GG – FIM). The red line indicates the mean difference, and blue lines mark the upper and lower bounds within ± 2 standard deviations of the mean difference. Abbreviations: FIM: Functional Independence Measure. Alt Text: Figure 2 presents Bland-Altman plots comparing Section GG and FIM scores for self-care and mobility at admission, discharge, and change, visualizing the agreement and bias between the two functional assessment methods.

Discussion

The observed alignment in clinician scores for self-care and transfer between standardized Section GG and site-specific FIM data suggests that most inpatient rehabilitation providers are accurately reporting patient function based on the instructions provided for each assessment. The general alignment between Section GG and FIM scores, regardless of assessment timing or impairment type, reinforces the reliability of both tools in functional assessment. However, our recommendation stands for future studies to consider the variations in functional score distributions when analyzing Section GG data across different impairments. The tendency for patients to be scored as more independent using Section GG compared to FIM is notable. This is because Section GG’s scoring methodology considers patients independent even with the use of assistive devices. Section GG also offers a more nuanced scale that differentiates between patients who are fully dependent or require two-person assistance and those who can contribute some physical effort. This distinction often results in a score of 2 (substantial assistance) on Section GG versus a score of 1 (total assistance) on FIM for the latter group. Consequently, at both ends of the rating scale, Section GG tends to assign higher scores than FIM. It is important to note that these higher scores do not inherently indicate “better” patient function but rather reflect differences in the rating scale definitions.

Furthermore, Section GG scores are designed to reflect usual performance, while FIM scores capture the most dependent performance. This difference in focus naturally leads to Section GG scores tending to be higher. Additionally, there might be an incentive for facilities to report the most dependent performances (e.g., during an evening shift), as lower FIM scores can result in patient classifications into higher-paying CMS categories.

Our findings also indicate that Section GG appears to be more sensitive in discriminating among patients with lower self-care and transfer abilities, whereas FIM is more discriminating for patients with higher abilities in these areas. This difference likely stems from the relative difficulty of items within each assessment. For example, FIM transfer items include the more challenging tub/shower transfer, which is absent in Section GG, where toilet transfer is the most challenging item.17,18 Section GG self-care includes more items and rating scale categories that are better suited to differentiate among less able patients, while FIM transfer has more items and categories that are better at differentiating among higher-functioning patients. These factors—differences in rating scale categories and definitions, item difficulty levels, and the focus on usual versus most dependent performance—collectively contribute to the observed differences between the two assessments.

The stronger correlations observed in self-care scores compared to transfer scores between Section GG and FIM might be attributed to a greater degree of content alignment in self-care items than in transfer items. Moreover, GG mobility items were developed to capture patient abilities across the entire post-acute care spectrum, from long-term care and skilled nursing facilities to hospitals and home care settings. Thus, GG items tend to reflect a broader range of mobility performance than FIM items, which were initially designed primarily for inpatient rehabilitation. It is crucial to understand that this difference does not suggest one assessment is inherently more valid or accurate than the other. Rather, it reflects the distinct purposes for which each assessment was originally designed.

The stronger correlations observed in discharge scores compared to admission scores could partly be due to the non-normal score distributions at discharge for both assessments. Discharge scores tended to cluster within a narrower range of the 0-100 scale, which may amplify the impact of differences in item difficulty and the categorical distinctions between Section GG’s 6-point and FIM’s 7-point rating scales. Both Section GG and FIM self-care scores showed negative skewness, indicating that many patients achieved near-total independence in self-care by discharge. The pronounced ceiling effect seen in Section GG but not in FIM self-care items at discharge is likely a consequence of these rating scale category differences.

These data suggest that many patients are discharged while using assistive devices to independently perform self-care activities. For transfer activities at discharge, both Section GG and FIM scores were negatively skewed with apparent “ceiling” effects. For Section GG, the ceiling is at 100, while for FIM, it is around 80 (recalibrated scores). Practically, this suggests that based on Section GG, patients are mostly independent in toilet transfers (with or without assistive devices) at discharge, whereas FIM indicates that most patients still require assistance with the more challenging tub-shower transfer item.

Overall, the Bland-Altman plots reinforced other findings, showing that Section GG scores were generally higher than FIM scores at both admission and discharge for self-care and transfers. Neither assessment showed evidence of systematic bias. Scores falling outside the limits of agreement likely reflect the nuanced issues related to rating scale categories and definitions, item difficulty, and the focus on usual versus most dependent performance, as previously discussed.

Finally, our study provides a valuable algorithm for identifying implausible scoring, contributing significantly to the analysis of similar functional data in inpatient rehabilitation settings. We found a discordance rate of 11-27% in self-care and 11-42% in transfer scores between the two assessments. During 2017, the period of our data collection, IRFs were compensated for reporting Section GG scores but not directly for patient performance on quality measures. This might have limited the incentive to ensure the utmost accuracy of Section GG scores. Conversely, during the same period, facility payments were largely determined by patient case-mix groupings, primarily based on FIM scores at admission. This likely created a stronger incentive to ensure FIM score accuracy and to report the most dependent performances at admission. Our algorithm offers an effective method for identifying inconsistent functional data reporting in future studies involving Section GG and FIM.

The ongoing transition to Section GG and its implications for the IRF prospective payment system, as well as for patient evaluation, treatment, and reimbursement, remain areas needing further research. Evaluating response patterns between Section GG and FIM is essential for establishing baseline evidence to understand the impact of adopting standardized functional data for quality reporting and payment mechanisms across post-acute care settings.

Study Limitations

CMS is continually updating items within standardized functional assessments across post-acute care settings. Our data reflects Section GG items as they appeared in IRF-PAI version 1.4, mandated in October 2016. While the most current IRF-PAI version is 4.0 (effective October 2020), we found no significant changes in the items analyzed in our study. Therefore, our findings remain relevant for examining standardized functional outcomes. Second, we only used six of the 17 Section GG mobility items to calculate transfer scores. This limitation, due to the study’s focus, may restrict our comprehensive understanding of the broader spectrum of mobility performance. Future research should address missing data in Section GG mobility items both conceptually and methodologically. Additionally, UDSMR data, collected primarily for billing purposes, does not allow us to control for potential confounders such as rater bias. This study, like all studies using retrospective data, has inherent limitations.19–21 For example, we are restricted to analyzing variables available within the UDSMR system, potentially limiting the depth of case-mix and facility-level data. However, it is important to note that the UDSMR system encompasses a significant majority of IRF data nationwide.10

Conclusions and Implications

This study serves as an initial step in understanding the transition to, and application of, standardized functional data for quality reporting in IRFs. We observed that clinician-observed scores in Section GG and FIM generally aligned, irrespective of evaluation timing or patient impairment. This suggests that most IRF providers are reporting patient function accurately based on the guidelines of each assessment. While patients tended to receive higher functional independence scores with Section GG compared to FIM, these higher scores primarily reflect differences in the rating scales rather than indicating “better” function. We recommend future studies to replicate this analysis in other post-acute care settings, such as skilled nursing facilities or home health agencies. Such research is crucial to determine whether Section GG can effectively maintain the quality and outcomes of post-acute services and support treatment planning across diverse healthcare settings.

Supplementary Material

mmc

NIHMS1791453-supplement-mmc.docx (105.5KB, docx)

Acknowledgments:

The authors extend their gratitude to Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, a board-certified Editor in the Life Sciences (bels.org), at the Sealy Center on Aging, University of Texas Medical Branch, for her invaluable assistance in reviewing and editing this manuscript prior to submission, provided without salary compensation.

Dedicated in memory of Carl V. Granger, MD, founder of the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation.

Funding Disclosure:

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P2CHD065702, K01HD101589).

Abbreviations

CMS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

FIM® Functional Independence Measure

IMPACT Act Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014

IRF Inpatient rehabilitation facilities

IRF-PAI Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument

IRF-PPS Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System

MedPAC Medicare Payment Advisory Commission

SPADEs Standardized patient assessment data elements

UDSMR® Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation

Footnotes

Publisher’s Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclaimer: All authors affirm that they adhere to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship guidelines and have no conflicts of interest to disclose regarding the publication of this paper.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

mmc

NIHMS1791453-supplement-mmc.docx (105.5KB, docx)