Microfluidic devices are revolutionizing point-of-care (POC) diagnostics by automating complex laboratory procedures in compact, user-friendly formats. Within these devices, check valves play a crucial role, ensuring unidirectional fluid flow necessary for precise sample handling and reagent delivery. However, a significant challenge remains: the need for a check valve design easily adaptable across all stages of device development, from initial laser-cut prototypes to high-volume injection-molded production, particularly in rigid thermoplastic materials. This article introduces a straightforward, passive check valve design crafted from readily available materials using CO2 laser technology, seamlessly integrating into both prototype and mass-produced thermoplastic microfluidic devices.

Understanding the Need for Simple Check Valves in Microfluidics

The advancement of microfluidics has been pivotal in shifting medical diagnostics towards point-of-care settings. Microfluidic technologies minimize equipment size and automate intricate reagent manipulations, making diagnostics more accessible and efficient. Among microfluidic components, valves are essential for directing fluid flow, and check valves are particularly valuable. They ensure one-way flow, enabling controlled, staged delivery of samples and reagents into designated areas within the device.

Currently, there’s a gap in readily available, mass-manufacturable passive check valve solutions that can be used from the initial design phase through to final injection molding production. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) based microfluidic devices, often utilizing Quake-style valves, are common in research. Quake valves, which use pressure-actuated control lines, are effective in PDMS but are less practical for commercial POC diagnostics due to the higher costs associated with photolithography production compared to injection molding. Furthermore, Quake valves are active valves, requiring external actuation mechanisms, which is not ideal for low-cost, disposable commercial products typically made from rigid thermoplastics like PMMA, COC, polycarbonate, and polypropylene.

Alternative approaches, such as rotary multiport valves or overmolded cracking pressure valves, exist but often involve active components or complex manufacturing processes. Rotary valves necessitate stepper motors, while overmolded valves demand precise tolerances to prevent leaks or excessively high cracking pressures. Other designs like terminal, bridge, tube and sleeve, and elastic slit check valves often rely on precise stretching of elastomers during assembly, leading to high failure rates in early prototyping due to material variations and assembly inconsistencies. Therefore, a need persists for a normally closed, passive check valve design that is easily integrated into thermoplastic devices throughout product development.

Introducing a Novel Laser-Cut Thermoplastic Check Valve

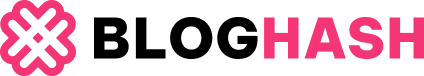

To address this need, we developed a check valve based on a laser-patterned thermoplastic film forming an orthoplanar spring. This spring applies a controlled force to a soft elastomer pad positioned over a fluid inlet hole (Fig. 1). Our design draws inspiration from earlier work using SU8 orthoplanar springs, but improves upon it by pre-stressing the valve springs, ensuring robust sealing against backflow. This pre-stressing is achieved by incorporating a separate soft elastomeric disc at the spring’s center and carefully designing the valve housing geometry. This innovative approach allows for the creation of reliably sealing check valves with springs cut from flat thermoplastic sheets, broadening the applicability of this valve type in POC microfluidics.

These novel check valves are compatible with both layer-by-layer assembled prototype chips and precision-machined microfluidic cartridges. They offer several advantages: passive and repeatable actuation, tunable opening pressure adjustable by modifying the spring’s geometry and thickness, and low dead volume (<1.6 μL). This article details the design and application of these simple micro check valves in three key areas: staged reagent delivery, finger-powered pneumatic pumping, and sealing a laser-cut chip for portable RNA detection of West Nile virus (WNV) using reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP).

Fabrication and Integration Methods for Thermoplastic Check Valves

Materials and Fabrication Process

For valve fabrication, we utilized readily available materials: acrylic (PMMA), PET (mylar), and contact adhesive. Soft silicone sheets were used for the elastomeric pads. Valve and chip designs were created using CAD software, and valves were fabricated using a CO2 laser cutter. Machined valve housings were prepared from cast PMMA. Elastomer discs were cast from EcoFlex silicone.

Laser-cut devices were assembled layer-by-layer after cleaning. Silicones were bonded to PMMA using a polyoleifin primer and cyanoacrylate adhesive. For machined housings, valves were assembled by dropping components into place and using a press-fit plug for a tight seal. Assembled valves were visualized using microscopy. Dead volume was experimentally measured by filling valves with water and measuring the mass.

Measuring Valve Performance: Opening Pressures

Valve opening pressures were measured using a syringe-based method. Air pressure was applied to the valve inlet until air bubbles appeared downstream in soapy water. Pressure was calculated based on volume change. This method was validated using a low-pressure regulator. Leak testing was performed by applying reverse pressure up to 275 kPa.

Demonstrating Applications of Simple Check Valves

Sequential Reagent Delivery and Finger-Actuated Pump

To demonstrate staged reagent delivery, we created a chip with integrated check valves and reagent reservoirs (Fig. 4A). Colored dyes were sequentially dispensed into a common reservoir using finger pressure. The check valves effectively prevented backflow and allowed for controlled, metered delivery.

A finger-actuated pump was created using two check valves in series, resembling a “microfluidic frog” (Fig. 4B). Pressing the “frog’s eyes” pumped air into a “throat,” demonstrating the valves’ capability for creating simple pneumatic pumps. The valves ensured one-directional airflow, enabling repeated pumping action.

RT-LAMP Detection of West Nile Virus with Integrated Check Valves

We applied these check valves to a laser-cut chip designed for RT-LAMP detection of West Nile virus RNA (Fig. 5). The chip was pre-filled with dried reagents, and the check valve was used to seal the reaction channels after rehydration with sample and buffer.

The check valve sealed the device, preventing evaporation during heating at 65°C for 30 minutes for RT-LAMP. The QUASR endpoint detection method provided reliable results, demonstrating the valve’s effectiveness in sealing microfluidic devices for diagnostic assays. This application highlights the potential of these simple check valves for enabling portable, point-of-care molecular diagnostics.

Valve Design and Performance: Key Parameters

Valve Fabrication and Integration Insights

Our check valves comprise an orthoplanar spring, an elastomer pad, and a valve housing (Fig. 1). The orthoplanar spring, laser-patterned from thin thermoplastic, provides the restoring force. The soft elastomer pad ensures a high-integrity seal over the fluid inlet. The valve housing, laser-engraved or machined, contains these components and minimizes dead volume. A raised annular boss in the housing enhances the seal.

Two integration approaches were explored: layer-by-layer assembly and engraved valve housings. Layer-by-layer assembly used through-cut thermoplastic and adhesive layers. Engraved housings involved laser-engraving PMMA pieces, offering reduced dead volume and fewer adhesive layers. Machined housings provided precise control over valve geometry.

Stereomicroscopic images (Fig. 2) show valves integrated into laser-cut and machined devices. PET, when laser-cut, created melt ridges that enhanced sealing. Engraved housings with countersunk spring perimeters and annular bosses further improved seal integrity and reduced dead volume.

Impact of Design Parameters on Opening Pressure

Valve opening pressure is tunable by adjusting the orthoplanar spring design, material stiffness, and thickness (Fig. 3). Different spring patterns, adapted from previous research, dramatically altered opening pressure. PET springs generally opened at lower pressures than PMMA springs of similar thickness due to PMMA’s higher elastic modulus. Thinner PET springs (0.13 mm) exhibited significantly lower opening pressures compared to thicker (0.25 mm) PET springs.

) and material. Spring patterns are shown underneath their corresponding data and name designation. Experiments were performed with triplicate measurements from at least 6 independently constructed valves. Valves were considered open when pressurized air was seen to pass through the valve outlet into soapy water, creating small bubbles. No valves leaked under reverse pressure.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/c030/5089928/7c746b914ae9/nihms824651f3.jpg)

Inlet hole diameter, elastomer stiffness (durometer), and elastomer thickness had less impact on opening pressure. Softer elastomers (10A durometer) provided the most consistent and leak-proof performance. Pre-stress, controlled by elastomer thickness, influenced opening pressure, with increased thickness leading to higher opening pressures. These valves demonstrated robust leak-proof sealing up to 275 kPa.

Conclusion: Simple Check Valves for Advanced Microfluidic POC Devices

This work introduces a simple, robust, and adaptable check valve design for microfluidic point-of-care diagnostics. These passive, normally closed valves are easily fabricated using laser cutting and integrate seamlessly into both prototype and mass-produced thermoplastic devices. The tunable opening pressure, achieved through spring design and material selection, and the valve’s ability to provide reliable sealing, make this design highly valuable for a range of microfluidic applications, including staged reagent delivery, pumping, and integrated diagnostic assays. The ease of prototyping and potential for mass production using injection molding position these simple check valves as a significant advancement for point-of-care diagnostic device development.